Blog

Genesis 17 – God traumatises His own creation

- April 2, 2025

- Posted by: Michael Hallett

- Category: Cornerstones

Genesis 17 is one of the most provocative chapters of the Bible—God’s instruction to Abraham to circumcise himself and his people as a promise of faithfulness.

The Bible account relates that the Lord appeared to Abraham and said: “You and all future members of your family must promise to obey me. As the sign that you are keeping this promise, you must circumcise every man and boy in your family.” (Genesis 17:9-11, Contemporary English Version)

The CEV dates this event to sometime after 1900 BC. Even if we accept Genesis 17 as historically accurate (which scholars doubt), the practice is much older.

Origins of circumcision

Circumcision is the oldest known surgical procedure, though its dating is inexact. Wikipedia claims that circumcision is depicted in Palaeolithic art though the reference they cite, a study by Javier Angulo and Marcos García-Díez, is equivocal:

“The genital representations performed in Europe during the Upper Palaeolithic period (38,000-11,000 years ago) allow us to infer the possible existence of a prehistoric practice of penile foreskin retraction or even circumcision.”

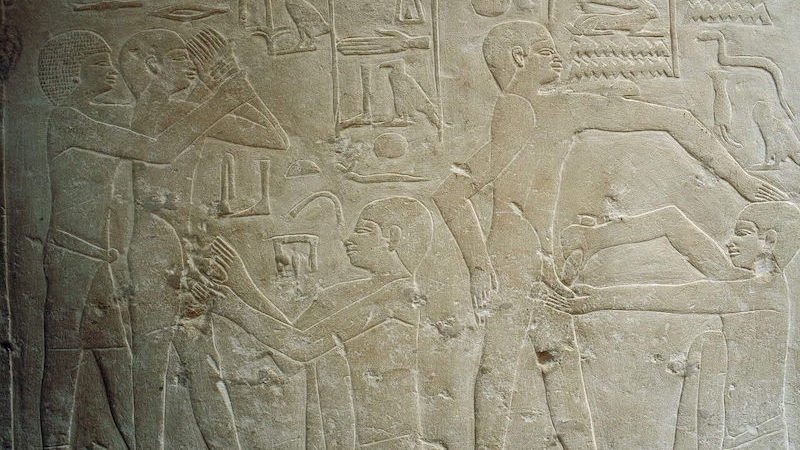

In Saharasia, geographer James DeMeo writes that “the earliest unambiguous evidence for circumcision comes from Egypt’s 6th Dynasty” (ca. 2300 BC) in a bas-relief in the pyramid of Ankhmahor at Saqqara.

In The Harlot by the Side of the Road, Jonathan Kirsch writes that “circumcision was… practiced by the Egyptians and many of the native-dwelling peoples of Canaan… the Bible identifies only the Philistines [‘Sea peoples’ from Greece] as uncircumcised.”

On the motive, Wikipedia states: “It has been speculated that circumcision originated as a substitute for castration of defeated enemies or as a religious sacrifice” as Genesis 17 describes.

Slavery

Like circumcision, slavery predates written history but became widespread with the advent of patriarchy. Testimony by the captain of an Egyptian vessel in the campaigns against the Hyksos (16th century BC) reads:

“Then Avaris was despoiled. Then I carried off spoil from there: one man, three women, a total of four persons; then his majesty gave them to me to be slaves.”

Male slaves were very useful, but they came with a risk: sex. Dominant cultures were obsessed with protecting their victorious bloodlines. Male slaves in elite households had potential access to women of the ruling class. That could not be permitted.

The obvious solution was castration. But castration caused heavy blood loss, resulting in high mortality. In History of Circumcision Peter Remondino claims that the mortality rate among slave boys castrated by Coptic monks in the Sudan was 90%.

Circumcision was a compromise that kept slaves in their place.

Insult sensitivity

DeMeo’s research reveals a high correlation between slavery and genital mutilation. These also correlate with an extreme sensitivity to insult. In other words, cultures that practiced slavery and genital mutilation were highly attuned to shame. They inflicted it on their enemies and avoided it themselves—at all costs.

The most disgraceful form of shame was—and still is—sexual shame.

One means of inflicting shame was enforced nudity. The Bible contains several references to the humiliation of public nudity:

“Hanun arrested David’s officials and had their beards shaved off on one side of their faces. He had their robes cut off just below the waist, and then he sent them away. They were terribly ashamed.” (2 Samuel 10:4-5)

“You will suffer the shame of going naked.” (Isaiah 47:3)

“I’ll rip off your clothes and leave you naked and ashamed.” (Jeremiah 13:27)

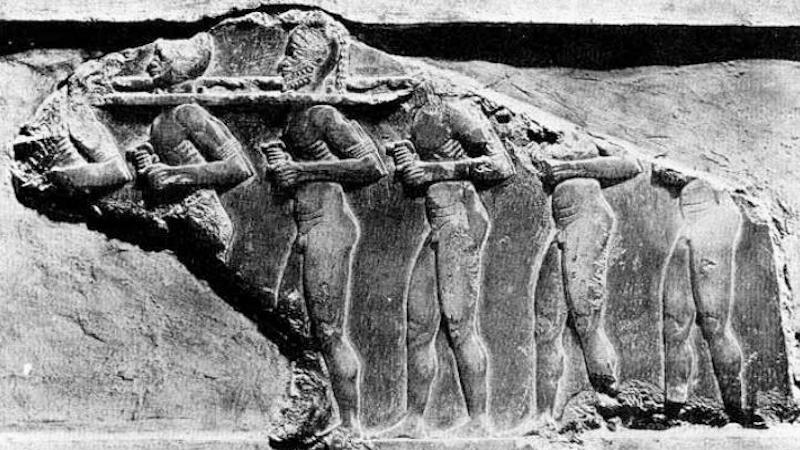

Forcing male slaves to go naked humiliated them and revealed their circumcision for all the world to see. It was the ineradicable mark of a slave. The stela above shows naked male slaves in the 3rd millennium BC, believed to be Akkadian captives.

The history of the early patriarchies shows that tribes, cultures, and empires rose and fell with bewildering rapidity. Victors became vanquished and vice-versa. The shamed became the shamers—but also had to deal with the fact that they bore the shameful mark of circumcision. The ineradicable had to be eradicated.

Genesis 17

The plight of the Israelites—from exile in Egypt to ruling their own kingdom to conquest by Babylon (the period when Genesis is thought to have been written)—neatly illustrates this.

In societies with extreme insult sensitivity, the shame of circumcision was intolerable. Yet the physical incision could not be undone for a generation. How do you remove the shame?

You reframe it as something socially desirable—even godly.

In The Oxford History of the Biblical World, Lawrence E. Stager writes:

“Contrast with those outside the group highlighted [identity]… this took the form of various contrastive rituals given the force of religious injunctions, such as circumcision and the pig taboo in food.”

It seems clear the Israelites were circumcised in captivity in Egypt. Following their exile the practice was adopted as a sign of cultural identity, which required the fabrication of Genesis 17—circumcision as divine instruction—to remove the stigma of slavery.

Yet removing the shame of circumcision did not remove its psychic impact.

Psychic wound

Historically, circumcision was intended to inflict profound psychosexual pain—deep enough to stop you messing with your enemy’s women. Moses Maimonides, physician and rabbi of Cairo (ca. 1175) writes:

“The true purpose of circumcision was to give the sexual organ that kind of physical pain as not to impair its natural function or the potency of the individual, but to lessen the power of passion and of too great desire.”

Circumcision turned sex into a psychologically traumatic act because it triggered a somatic (body) memory of the pain of the procedure. That pain became embedded in the collective psyche, passed down through generational trauma.

As DeMeo demonstrates in Saharasia, the violent cultures descended from the early patriarchies of the near east gradually conquered the world, taking this psychic wound with them—whether they practiced circumcision or not.

Which is why Genesis 17 is still relevant today.

The psychic wound of circumcision is part of the rejection and shaming of the entire sexual aspect of humanity that Michael Picucci calls the ‘sexual-spiritual split’.

In The Journey Toward Complete Recovery he describes it as “a deep psychic schism within almost everyone in our culture” which teaches that, “God, love and family are good while sex is dirty, bad and perverse.”

This is the core sexual wound at the heart of fallen humanity.

Everything that happened 6,000 years ago at the dawn of patriarchy is still happening today, just in a deeply buried, subterranean way—because no one has healed it.

God traumatises His own creation

The emotional history of the Biblical age reveals a clear functional drive for circumcision to arise as a means of sexually incapacitating slaves, followed by an equally clear need for the practice to become a religious sacrifice to reframe the shame of slavery.

The alternative view—that God one day decided to demand that Abraham circumcise all his people as a random loyalty test, traumatising their God-given sexual wholeness—makes no sense.

This does not invalidate Genesis, the Bible, or God. It makes sense of an otherwise inexplicable instruction from God to traumatise His own creation. I believe Genesis 17 was created as an instructional text to provide a foundation for ritual circumcision. The practice had to come from somewhere.

The relevance of Genesis 17 lies in bringing the ancestral wound of circumcision into our current awareness. On the road to healing ancestral traumas and restoring healthy, God-given sexuality we must contend with the psychic legacy of genital mutilation in all its forms.

Image: Unknown stela, believed to show Akkadian war captives (third millennium BC). Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2400-2300 BC) is considered the world’s first emperor.